Ever wondered what happens when Sidekiq calls redis.brpop() and your thread magically “blocks” until a job appears? The answer lies in one of computing’s most fundamental concepts: sockets. Let’s dive deep into this invisible infrastructure that powers everything from your Redis connections to Netflix streaming.

🚀 What is a Socket?

A socket is essentially a communication endpoint – think of it like a “phone number” that programs can use to talk to each other.

Application A ←→ Socket ←→ Network ←→ Socket ←→ Application B

Simple analogy: If applications are people, sockets are like phone numbers that let them call each other!

🎯 The Purpose of Sockets

📡 Inter-Process Communication (IPC)

# Two Ruby programs talking via sockets

# Program 1 (Server)

require 'socket'

server = TCPServer.new(3000)

client_socket = server.accept

client_socket.puts "Hello from server!"

# Program 2 (Client)

client = TCPSocket.new('localhost', 3000)

message = client.gets

puts message # "Hello from server!"

🌐 Network Communication

# Talk to Redis (what Sidekiq does)

require 'socket'

redis_socket = TCPSocket.new('localhost', 6379)

redis_socket.write("PING\r\n")

response = redis_socket.read # "PONG"

🏠 Are Sockets Only for Networking?

NO! Sockets work for both local and network communication:

🌍 Network Sockets (TCP/UDP)

# Talk across the internet

require 'socket'

socket = TCPSocket.new('google.com', 80)

socket.write("GET / HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: google.com\r\n\r\n")

🔗 Local Sockets (Unix Domain Sockets)

# Talk between programs on same machine

# Faster than network sockets - no network stack overhead

socket = UNIXSocket.new('/tmp/my_app.sock')

Real example: Redis can use Unix sockets for local connections:

# Network socket (goes through TCP/IP stack)

redis = Redis.new(host: 'localhost', port: 6379)

# Unix socket (direct OS communication)

redis = Redis.new(path: '/tmp/redis.sock') # Faster!

🔢 What Are Ports?

Ports are like apartment numbers – they help identify which specific application should receive the data.

IP Address: 192.168.1.100 (Building address)

Port: 6379 (Apartment number)

🎯 Why This Matters

Same computer running:

- Web server on port 80

- Redis on port 6379

- SSH on port 22

- Your app on port 3000

When data arrives at 192.168.1.100:6379

→ OS knows to send it to Redis

🏢 Why Do We Need So Many Ports?

Think of a computer like a massive apartment building:

🔧 Multiple Services

# Different services need different "apartments"

$ netstat -ln

tcp 0.0.0.0:22 SSH server

tcp 0.0.0.0:80 Web server

tcp 0.0.0.0:443 HTTPS server

tcp 0.0.0.0:3306 MySQL

tcp 0.0.0.0:5432 PostgreSQL

tcp 0.0.0.0:6379 Redis

tcp 0.0.0.0:27017 MongoDB

🔄 Multiple Connections to Same Service

Redis server (port 6379) can handle:

- Connection 1: Sidekiq worker

- Connection 2: Rails app

- Connection 3: Redis CLI

- Connection 4: Monitoring tool

Each gets a unique "channel" but all use port 6379

📊 Port Ranges

0-1023: Reserved (HTTP=80, SSH=22, etc.)

1024-49151: Registered applications

49152-65535: Dynamic/Private (temporary connections)

⚙️ How Sockets Work Internally

🛠️ Socket Creation

# What happens when you do this:

socket = TCPSocket.new('localhost', 6379)

Behind the scenes:

// OS system calls

socket_fd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0) // Create socket

connect(socket_fd, server_address, address_len) // Connect

📋 The OS Socket Table

Process ID: 1234 (Your Ruby app)

File Descriptors:

0: stdin

1: stdout

2: stderr

3: socket to Redis (localhost:6379)

4: socket to PostgreSQL (localhost:5432)

5: listening socket (port 3000)

🔮 Kernel-Level Magic

Application: socket.write("PING")

↓

Ruby: calls OS write() system call

↓

Kernel: adds to socket send buffer

↓

Network Stack: TCP → IP → Ethernet

↓

Network Card: sends packets over wire

🌈 Types of Sockets

📦 TCP Sockets (Reliable)

# Like registered mail - guaranteed delivery

server = TCPServer.new(3000)

client = TCPSocket.new('localhost', 3000)

# Data arrives in order, no loss

client.write("Message 1")

client.write("Message 2")

# Server receives exactly: "Message 1", "Message 2"

⚡ UDP Sockets (Fast but unreliable)

# Like shouting across a crowded room

require 'socket'

# Sender

udp = UDPSocket.new

udp.send("Hello!", 0, 'localhost', 3000)

# Receiver

udp = UDPSocket.new

udp.bind('localhost', 3000)

data = udp.recv(1024) # Might not arrive!

🏠 Unix Domain Sockets (Local)

# Super fast local communication

File.delete('/tmp/test.sock') if File.exist?('/tmp/test.sock')

# Server

server = UNIXServer.new('/tmp/test.sock')

# Client

client = UNIXSocket.new('/tmp/test.sock')

🔄 Socket Lifecycle

🤝 TCP Connection Dance

# 1. Server: "I'm listening on port 3000"

server = TCPServer.new(3000)

# 2. Client: "I want to connect to port 3000"

client = TCPSocket.new('localhost', 3000)

# 3. Server: "I accept your connection"

connection = server.accept

# 4. Both can now send/receive data

connection.puts "Hello!"

client.puts "Hi back!"

# 5. Clean shutdown

client.close

connection.close

server.close

🔄 Under the Hood (TCP Handshake)

Client Server

| |

|---- SYN packet -------->| (I want to connect)

|<-- SYN-ACK packet ------| (OK, let's connect)

|---- ACK packet -------->| (Connection established!)

| |

|<---- Data exchange ---->|

| |

🏗️ OS-Level Socket Implementation

📁 File Descriptor Magic

socket = TCPSocket.new('localhost', 6379)

puts socket.fileno # e.g., 7

# This socket is just file descriptor #7!

# You can even use it with raw system calls

🗂️ Kernel Socket Buffers

Application Buffer ←→ Kernel Send Buffer ←→ Network

←→ Kernel Recv Buffer ←→

What happens on socket.write:

socket.write("BRPOP queue 0")

# 1. Ruby copies data to kernel send buffer

# 2. write() returns immediately

# 3. Kernel sends data in background

# 4. TCP handles retransmission, etc.

What happens on socket.read:

data = socket.read

# 1. Check kernel receive buffer

# 2. If empty, BLOCK thread until data arrives

# 3. Copy data from kernel to Ruby

# 4. Return to your program

🎯 Real-World Example: Sidekiq + Redis

# When Sidekiq does this:

redis.brpop("queue:default", timeout: 2)

# Here's the socket journey:

# 1. Ruby opens TCP socket to localhost:6379

socket = TCPSocket.new('localhost', 6379)

# 2. Format Redis command

command = "*4\r\n$5\r\nBRPOP\r\n$13\r\nqueue:default\r\n$1\r\n2\r\n"

# 3. Write to socket (goes to kernel buffer)

socket.write(command)

# 4. Thread blocks reading response

response = socket.read # BLOCKS HERE until Redis responds

# 5. Redis eventually sends back data

# 6. Kernel receives packets, assembles them

# 7. socket.read returns with the job data

🚀 Socket Performance Tips

♻️ Socket Reuse

# Bad: New socket for each request

100.times do

socket = TCPSocket.new('localhost', 6379)

socket.write("PING\r\n")

socket.read

socket.close # Expensive!

end

# Good: Reuse socket

socket = TCPSocket.new('localhost', 6379)

100.times do

socket.write("PING\r\n")

socket.read

end

socket.close

🏊 Connection Pooling

# What Redis gem/Sidekiq does internally

class ConnectionPool

def initialize(size: 5)

@pool = size.times.map { TCPSocket.new('localhost', 6379) }

end

def with_connection(&block)

socket = @pool.pop

yield(socket)

ensure

@pool.push(socket)

end

end

🎪 Fun Socket Facts

📄 Everything is a File

# On Linux/Mac, sockets appear as files!

$ lsof -p #{Process.pid}

ruby 1234 user 3u sock 0,9 0t0 TCP localhost:3000->localhost:6379

🚧 Socket Limits

# Your OS has limits

$ ulimit -n

1024 # Max file descriptors (including sockets)

# Web servers need thousands of sockets

# That's why they increase this limit!

📊 Socket States

$ netstat -an | grep 6379

tcp4 0 0 127.0.0.1.6379 127.0.0.1.50123 ESTABLISHED

tcp4 0 0 127.0.0.1.6379 127.0.0.1.50124 TIME_WAIT

tcp4 0 0 *.6379 *.* LISTEN

🎯 Key Takeaways

- 🔌 Sockets = Communication endpoints between programs

- 🏠 Ports = Apartment numbers for routing data to the right app

- 🌐 Not just networking – also local inter-process communication

- ⚙️ OS manages everything – kernel buffers, network stack, blocking

- 📁 File descriptors – sockets are just special files to the OS

- 🏊 Connection pooling is crucial for performance

- 🔒 BRPOP blocking happens at the socket read level

🌟 Conclusion

The beauty of sockets is their elegant simplicity: when Sidekiq calls redis.brpop(), it’s using the same socket primitives that have powered network communication for decades!

From your Redis connection to Netflix streaming to Zoom calls, sockets are the fundamental building blocks that make modern distributed systems possible. Understanding how they work gives you insight into everything from why connection pooling matters to how blocking I/O actually works at the system level.

The next time you see a thread “blocking” on network I/O, you’ll know exactly what’s happening: a simple socket read operation, leveraging decades of OS optimization to efficiently wait for data without wasting a single CPU cycle. Pretty amazing for something so foundational! 🚀

⚡ Inside Redis: How Your Favorite In-Memory Database Actually Works

You’ve seen how Sidekiq connects to Redis via sockets, but what happens when Redis receives that BRPOP command? Let’s pull back the curtain on one of the most elegant pieces of software ever written and discover why Redis is so blazingly fast.

🎯 What Makes Redis Special?

Redis isn’t just another database – it’s a data structure server. While most databases make you think in tables and rows, Redis lets you work directly with lists, sets, hashes, and more. It’s like having super-powered variables that persist across program restarts!

# Traditional database thinking

User.where(active: true).pluck(:id)

# Redis thinking

redis.smembers("active_users") # A set of active user IDs

🏗️ Redis Architecture Overview

Redis has a deceptively simple architecture that’s incredibly powerful:

┌─────────────────────────────────┐

│ Client Connections │ ← Your Ruby app connects here

├─────────────────────────────────┤

│ Command Processing │ ← Parses your BRPOP command

├─────────────────────────────────┤

│ Event Loop (epoll) │ ← Handles thousands of connections

├─────────────────────────────────┤

│ Data Structure Engine │ ← The magic happens here

├─────────────────────────────────┤

│ Memory Management │ ← Keeps everything in RAM

├─────────────────────────────────┤

│ Persistence Layer │ ← Optional disk storage

└─────────────────────────────────┘

🔥 The Single-Threaded Magic

Here’s Redis’s secret sauce: it’s mostly single-threaded!

// Simplified Redis main loop

while (server_running) {

// 1. Check for new network events

events = epoll_wait(eventfd, events, max_events, timeout);

// 2. Process each event

for (int i = 0; i < events; i++) {

if (events[i].type == READ_EVENT) {

process_client_command(events[i].client);

}

}

// 3. Handle time-based events (expiry, etc.)

process_time_events();

}

Why single-threaded is brilliant:

- ✅ No locks or synchronization needed

- ✅ Incredibly fast context switching

- ✅ Predictable performance

- ✅ Simple to reason about

🧠 Data Structure Deep Dive

📝 Redis Lists (What Sidekiq Uses)

When you do redis.brpop("queue:default"), you’re working with a Redis list:

// Redis list structure (simplified)

typedef struct list {

listNode *head; // First item

listNode *tail; // Last item

long length; // How many items

// ... other fields

} list;

typedef struct listNode {

struct listNode *prev;

struct listNode *next;

void *value; // Your job data

} listNode;

BRPOP implementation inside Redis:

// Simplified BRPOP command handler

void brpopCommand(client *c) {

// Try to pop from each list

for (int i = 1; i < c->argc - 1; i++) {

robj *key = c->argv[i];

robj *list = lookupKeyRead(c->db, key);

if (list && listTypeLength(list) > 0) {

// Found item! Pop and return immediately

robj *value = listTypePop(list, LIST_TAIL);

addReplyMultiBulkLen(c, 2);

addReplyBulk(c, key);

addReplyBulk(c, value);

return;

}

}

// No items found - BLOCK the client

blockForKeys(c, c->argv + 1, c->argc - 2, timeout);

}

🔑 Hash Tables (Super Fast Lookups)

Redis uses hash tables for O(1) key lookups:

// Redis hash table

typedef struct dict {

dictEntry **table; // Array of buckets

unsigned long size; // Size of table

unsigned long sizemask; // size - 1 (for fast modulo)

unsigned long used; // Number of entries

} dict;

// Finding a key

unsigned int hash = dictGenHashFunction(key);

unsigned int idx = hash & dict->sizemask;

dictEntry *entry = dict->table[idx];

This is why Redis is so fast – finding any key is O(1)!

⚡ The Event Loop: Handling Thousands of Connections

Redis uses epoll (Linux) or kqueue (macOS) to efficiently handle many connections:

// Simplified event loop

int epollfd = epoll_create(1024);

// Add client socket to epoll

struct epoll_event ev;

ev.events = EPOLLIN; // Watch for incoming data

ev.data.ptr = client;

epoll_ctl(epollfd, EPOLL_CTL_ADD, client->fd, &ev);

// Main loop

while (1) {

int nfds = epoll_wait(epollfd, events, MAX_EVENTS, timeout);

for (int i = 0; i < nfds; i++) {

client *c = (client*)events[i].data.ptr;

if (events[i].events & EPOLLIN) {

// Data available to read

read_client_command(c);

process_command(c);

}

}

}

Why this is amazing:

Traditional approach: 1 thread per connection

- 1000 connections = 1000 threads

- Each thread uses ~8MB memory

- Context switching overhead

Redis approach: 1 thread for all connections

- 1000 connections = 1 thread

- Minimal memory overhead

- No context switching between connections

🔒 How BRPOP Blocking Actually Works

Here’s the magic behind Sidekiq’s blocking behavior:

🎭 Client Blocking State

// When no data available for BRPOP

typedef struct blockingState {

dict *keys; // Keys we're waiting for

time_t timeout; // When to give up

int numreplicas; // Replication stuff

// ... other fields

} blockingState;

// Block a client

void blockClient(client *c, int btype) {

c->flags |= CLIENT_BLOCKED;

c->btype = btype;

c->bstate = zmalloc(sizeof(blockingState));

// Add to server's list of blocked clients

listAddNodeTail(server.clients, c);

}

⏰ Timeout Handling

// Check for timed out clients

void handleClientsBlockedOnKeys(void) {

time_t now = time(NULL);

listIter li;

listNode *ln;

listRewind(server.clients, &li);

while ((ln = listNext(&li)) != NULL) {

client *c = listNodeValue(ln);

if (c->flags & CLIENT_BLOCKED &&

c->bstate.timeout != 0 &&

c->bstate.timeout < now) {

// Timeout! Send null response

addReplyNullArray(c);

unblockClient(c);

}

}

}

🚀 Unblocking When Data Arrives

// When someone does LPUSH to a list

void signalKeyAsReady(redisDb *db, robj *key) {

readyList *rl = zmalloc(sizeof(*rl));

rl->key = key;

rl->db = db;

// Add to ready list

listAddNodeTail(server.ready_keys, rl);

}

// Process ready keys and unblock clients

void handleClientsBlockedOnKeys(void) {

while (listLength(server.ready_keys) != 0) {

listNode *ln = listFirst(server.ready_keys);

readyList *rl = listNodeValue(ln);

// Find blocked clients waiting for this key

list *clients = dictFetchValue(rl->db->blocking_keys, rl->key);

if (clients) {

// Unblock first client and serve the key

client *receiver = listNodeValue(listFirst(clients));

serveClientBlockedOnList(receiver, rl->key, rl->db);

}

listDelNode(server.ready_keys, ln);

}

}

💾 Memory Management: Keeping It All in RAM

🧮 Memory Layout

// Every Redis object has this header

typedef struct redisObject {

unsigned type:4; // STRING, LIST, SET, etc.

unsigned encoding:4; // How it's stored internally

unsigned lru:24; // LRU eviction info

int refcount; // Reference counting

void *ptr; // Actual data

} robj;

🗂️ Smart Encodings

Redis automatically chooses the most efficient representation:

// Small lists use ziplist (compressed)

if (listLength(list) < server.list_max_ziplist_entries &&

listTotalSize(list) < server.list_max_ziplist_value) {

// Use compressed ziplist

listConvert(list, OBJ_ENCODING_ZIPLIST);

} else {

// Use normal linked list

listConvert(list, OBJ_ENCODING_LINKEDLIST);

}

Example memory optimization:

Small list: ["job1", "job2", "job3"]

Normal encoding: 3 pointers + 3 allocations = ~200 bytes

Ziplist encoding: 1 allocation = ~50 bytes (75% savings!)

🧹 Memory Reclamation

// Redis memory management

void freeMemoryIfNeeded(void) {

while (server.memory_usage > server.maxmemory) {

// Try to free memory by:

// 1. Expiring keys

// 2. Evicting LRU keys

// 3. Running garbage collection

if (freeOneObjectFromFreelist() == C_OK) continue;

if (expireRandomExpiredKey() == C_OK) continue;

if (evictExpiredKeys() == C_OK) continue;

// Last resort: evict LRU key

evictLRUKey();

}

}

💿 Persistence: Making Memory Durable

📸 RDB Snapshots

// Save entire dataset to disk

int rdbSave(char *filename) {

FILE *fp = fopen(filename, "w");

// Iterate through all databases

for (int dbid = 0; dbid < server.dbnum; dbid++) {

redisDb *db = server.db + dbid;

dict *d = db->dict;

// Save each key-value pair

dictIterator *di = dictGetSafeIterator(d);

dictEntry *de;

while ((de = dictNext(di)) != NULL) {

sds key = dictGetKey(de);

robj *val = dictGetVal(de);

// Write key and value to file

rdbSaveStringObject(fp, key);

rdbSaveObject(fp, val);

}

}

fclose(fp);

}

📝 AOF (Append Only File)

// Log every write command

void feedAppendOnlyFile(struct redisCommand *cmd, int dictid,

robj **argv, int argc) {

sds buf = sdsnew("");

// Format as Redis protocol

buf = sdscatprintf(buf, "*%d\r\n", argc);

for (int i = 0; i < argc; i++) {

buf = sdscatprintf(buf, "$%lu\r\n",

(unsigned long)sdslen(argv[i]->ptr));

buf = sdscatsds(buf, argv[i]->ptr);

buf = sdscatlen(buf, "\r\n", 2);

}

// Write to AOF file

write(server.aof_fd, buf, sdslen(buf));

sdsfree(buf);

}

🚀 Performance Secrets

🎯 Why Redis is So Fast

- 🧠 Everything in memory – No disk I/O during normal operations

- 🔄 Single-threaded – No locks or context switching

- ⚡ Optimized data structures – Custom implementations for each type

- 🌐 Efficient networking – epoll/kqueue for handling connections

- 📦 Smart encoding – Automatic optimization based on data size

📊 Real Performance Numbers

Operation Operations/second

SET 100,000+

GET 100,000+

LPUSH 100,000+

BRPOP (no block) 100,000+

BRPOP (blocking) Limited by job arrival rate

🔧 Configuration for Speed

# redis.conf optimizations

tcp-nodelay yes # Disable Nagle's algorithm

tcp-keepalive 60 # Keep connections alive

timeout 0 # Never timeout idle clients

# Memory optimizations

maxmemory-policy allkeys-lru # Evict least recently used

save "" # Disable snapshotting for speed

🌐 Redis in Production

🏗️ Scaling Patterns

Master-Slave Replication:

Master (writes) ─┐

├─→ Slave 1 (reads)

├─→ Slave 2 (reads)

└─→ Slave 3 (reads)

Redis Cluster (sharding):

Client ─→ Hash Key ─→ Determine Slot ─→ Route to Correct Node

Slots 0-5460: Node A

Slots 5461-10922: Node B

Slots 10923-16383: Node C

🔍 Monitoring Redis

# Real-time stats

redis-cli info

# Monitor all commands

redis-cli monitor

# Check slow queries

redis-cli slowlog get 10

# Memory usage by key pattern

redis-cli --bigkeys

🎯 Redis vs Alternatives

📊 When to Choose Redis

✅ Need sub-millisecond latency

✅ Working with simple data structures

✅ Caching frequently accessed data

✅ Session storage

✅ Real-time analytics

✅ Message queues (like Sidekiq!)

❌ Need complex queries (use PostgreSQL)

❌ Need ACID transactions across keys

❌ Dataset larger than available RAM

❌ Need strong consistency guarantees

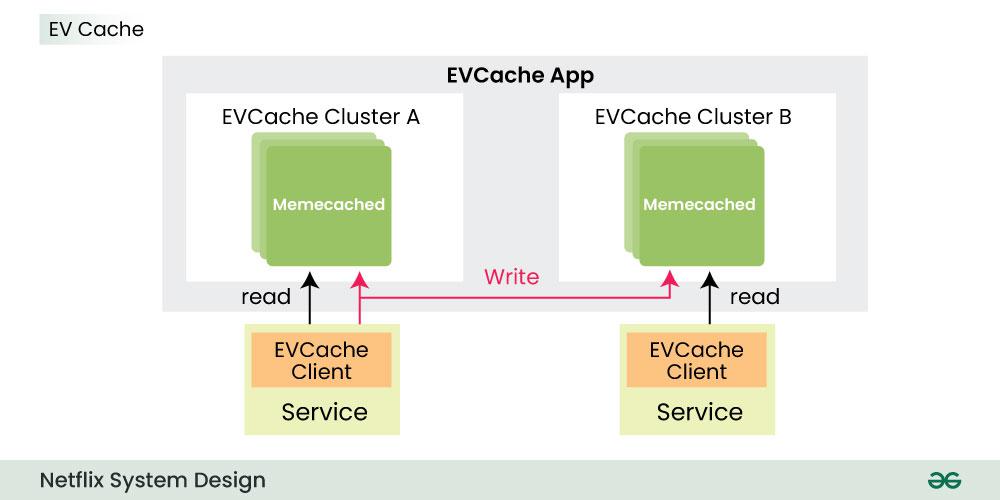

🥊 Redis vs Memcached

Redis:

+ Rich data types (lists, sets, hashes)

+ Persistence options

+ Pub/sub messaging

+ Transactions

- Higher memory usage

Memcached:

+ Lower memory overhead

+ Simpler codebase

- Only key-value storage

- No persistence

🔮 Modern Redis Features

🌊 Redis Streams

# Modern alternative to lists for job queues

redis.xadd("jobs", {"type" => "email", "user_id" => 123})

redis.xreadgroup("workers", "worker-1", "jobs", ">")

📡 Redis Modules

RedisJSON: Native JSON support

RedisSearch: Full-text search

RedisGraph: Graph database

RedisAI: Machine learning

TimeSeries: Time-series data

⚡ Redis 7 Features

- Multi-part AOF files

- Config rewriting improvements

- Better memory introspection

- Enhanced security (ACLs)

- Sharded pub/sub

🎯 Key Takeaways

- 🔥 Single-threaded simplicity enables incredible performance

- 🧠 In-memory architecture eliminates I/O bottlenecks

- ⚡ Custom data structures are optimized for specific use cases

- 🌐 Event-driven networking handles thousands of connections efficiently

- 🔒 Blocking operations like BRPOP are elegant and efficient

- 💾 Smart memory management keeps everything fast and compact

- 📈 Horizontal scaling is possible with clustering and replication

🌟 Conclusion

Redis is a masterclass in software design – taking a simple concept (in-memory data structures) and optimizing every single aspect to perfection. When Sidekiq calls BRPOP, it’s leveraging decades of systems programming expertise distilled into one of the most elegant and performant pieces of software ever written.

The next time you see Redis handling thousands of operations per second while using minimal resources, you’ll understand the beautiful engineering that makes it possible. From hash tables to event loops to memory management, every component works in harmony to deliver the performance that makes modern applications possible.

Redis proves that sometimes the best solutions are the simplest ones, executed flawlessly! 🚀